Type-writing ahead of time: John Galloway’s inventions

News Story

In the early 1800s, Paisley-born John Galloway immigrated to America. Through his letter home in 1868, we can see the progress of his type-writing inventions, years before the typewriter as we know it.

Modern typewriters like the Sholes and Glidden typewriter by E. Remington & Sons were first made in 1876. In the same year, The Times and the Glasgow Herald printed letters about the novelty of ‘the new machine called the type writer’.

Galloway's type-writing machines may not survive, but his letters and text samples give us an idea of how his inventions worked.

Our collection features a hand-written letter and type-written sample text by Paisley-born John Galloway in 1868, sent to his niece Margaret Corry.

Written from New York, the first half of the letter covers family news on both sides of the Atlantic. It then turns to quite other matters.

‘When I was young in comparison to what I now am, I took up the idea that some kind of machine could be made with keys, similar to those of a piano, to print letters, instead of writing them with a pen’.

Galloway to his niece

New apparatus

He explained that he had constructed: ‘an apparatus with which I accomplished that object, with the exception that the impression was made in relief, only, instead of being done with colour.’

Such embossed type, often aimed at those with impaired sight, was being explored by others in the first half of the 19th century. American Alfred Ely Beach produced a prototype in 1847 and a patent model in 1856. Piano keys also inspired others, including Samuel Francis of Rhode Island, who patented a machine in 1857.

Galloway told Corry that he still had some samples ‘made at the time’, but it is unclear exactly when that was. Certainly it was in Scotland, for he ‘left home shortly after, to come to America’ and had abandoned his project. Recent research suggests that Galloway was born in 1811 and living in New York by 1850, when he and his wife Janet were listed in the census with their baby son. Other records indicate that while both parents were born in Scotland, young William was born in America.

If the couple moved after marrying and before their son was born, Galloway may have been working on his machine in Paisley the 1840s. This would date his work before that of Peter Hood, who was working on a writing machine in Angus in the 1850s.

Galloway's machines then are potentially decades ahead of when recognisably modern typewriters first arrived in Scotland from America.

It is also interesting to note that a John Galloway published a short pamphlet entitled ‘A New System of Stenography’ in 1837. The pamphlet introduced a novel system of shorthand writing. If this was written by the inventor John Galloway, this suggests that he had long had an interest in systems of writing.

Revisiting his inventions

In 1868, Galloway told his niece that he had recently been thinking again about his machine. He had made another apparatus which printed the letter with ink. This was almost contemporary with a machine with piano-style keys, patented in June 1868 by Sholes, Glidden and Soule.

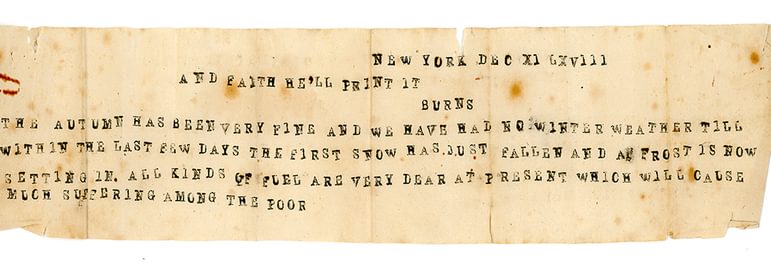

The sample of type that Galloway sent to Corry was from this second machine. It would, he said, have been better had it ‘been made by a regular machinist, and with proper materials.’

He had been working against the odds, while his wife was ill, but he felt that in better circumstances an improved and reasonably priced machine might be made and patented. He said:

‘It would surely be as easy and as speedy to operate upon keys with the fingers, as to write with a pen; the trouble of learning would be less and the composition would be more easily read than when done up in a rugged scrawl.’

Galloway had actually written his letter in a beautifully regular hand, while his machine produced some rather bumpy lines of upper-case letters. It is likely that, as with other early machines including the Scholes and Glidden, there was no lower case.

The sample text opens with a line from fellow Scotsman Robert Burns: ‘And faith he'll print it.’ The main content comments on the weather. The fine and long autumn had recently turned to winter cold. The high fuel costs would ensure 'much suffering among the poor’.

Galloway did not go on to patent this invention, and things do seem to have been difficult for the family at the time, his wife dying not long after. He told his niece that William was about to move out west due to lack of opportunities for young men in New York. He added that:

‘Rents are so outrageously high here, and all the necessaries of life are so high also, that it requires great exertion to make a decent livelihood. We find it difficult to make any headway, notwithstanding all our efforts.’

Later prototypes

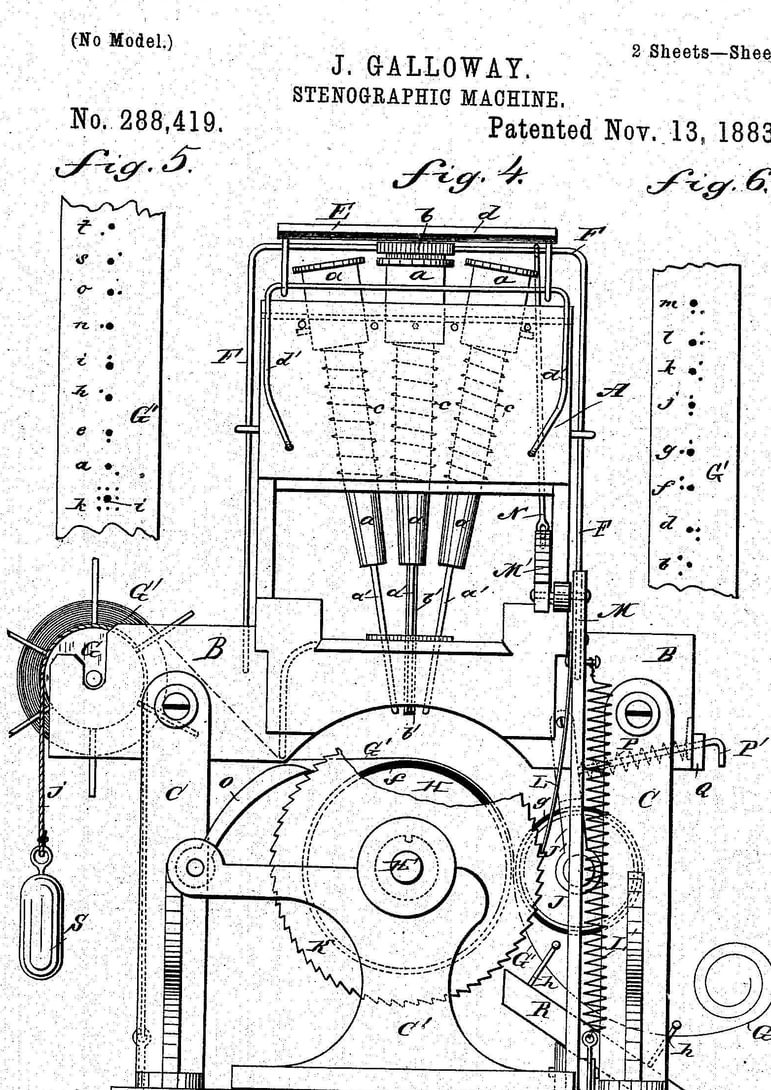

In 1850, John Galloway was a Grocer. He was a Bookseller in 1860, and by 1868 his son William was helping him in the store. He had retired by 1880, but the two younger sons continued the business as clerks in the store. Galloway kept inventing. He was granted two patents in New York, one in 1873 for an ‘Improvement in Type-Writing Machines’ and one in 1883 for a stenographic machine.

The later machines were different to Galloway’s earlier prototypes, with piano-style keys long gone. It is likely that Galloway’s 1868 machine had ink applied directly to the type, but the stenographic shorthand machine of 1883 could be used with an ‘inking-ribbon’.

Galloway was a forward-thinker, and his original ideas have stood the test of time. His 1883 machine, for example, was ‘especially intended for the blind’. In the 1970s, The Writing Machine described Galloway's prototypes as being ‘almost identical’ to the machines patented and manufactured by Burridge and Odell over a decade later.

John Galloway's legacy

Galloway's machines did not move beyond prototype, and as far as we know do not survive today. However, they are a fascinating addition to our knowledge early efforts in the field of typewriting.

We know little more of John Galloway, except that his nephew William was also an inventor and a successful mining engineer. William’s research and innovations led to a professorship and a knighthood.

While John’s inventive spirit did not give him this kind of recognition, more research may yet reveal more about him and his machines.